Results

Alex Hildred

Trench 1 Excavation Outboard of the Transom

Introduction

The sternpost was the first point recognised when the ROV was deployed. The sternpost protruded above the surrounding seabed 550mm on the port side but there was no sign of a rudder or rudder pintles. The sternpost clearly lay angled to the port side, and the port side structure outboard was just visible at seabed level. Just inboard was an iron gun (3 ½” / 89mm bore) and an unquantified number of lead ingots, many of which were firmly imbedded into concretion.

It was decided to use the stern planking as a guide and excavate from the junction of the sternpost and planking on the port side to the junction with the port side as shown in previous excavations. The excavation was extended backwards (further outboard) to define the edge of the previous excavation trenches and to enable room to excavate. Towards the starboard side we found concretion, nets and chain which would have been a major task to remove. This prompted us to move inboard towards the bow rather than to attempt to locate the junction with the starboard side at the stern. This debris did not merely surround the sternpost but extended outboard away from the ship in places up to 3m away from the hull. The trench extended over two metres away from the vessel to a depth of 2.5m by the sternpost, but only 800mm at the junction with the port side. A total of seventy dives were spent in Trench 1. Excavation was halted when concretions were encountered which to excavate would entail undermining the structure. There were still collapsed structural elements visible amongst the concretions.

It was decided to use the stern planking as a guide and excavate from the junction of the sternpost and planking on the port side to the junction with the port side as shown in previous excavations. The excavation was extended backwards (further outboard) to define the edge of the previous excavation trenches and to enable room to excavate. Towards the starboard side we found concretion, nets and chain which would have been a major task to remove. This prompted us to move inboard towards the bow rather than to attempt to locate the junction with the starboard side at the stern. This debris did not merely surround the sternpost but extended outboard away from the ship in places up to 3m away from the hull. The trench extended over two metres away from the vessel to a depth of 2.5m by the sternpost, but only 800mm at the junction with the port side. A total of seventy dives were spent in Trench 1. Excavation was halted when concretions were encountered which to excavate would entail undermining the structure. There were still collapsed structural elements visible amongst the concretions.

Structure

Sternpost and Transom Survey

The sternpost has an external width of 520mm and is racked outwards from top to bottom at an angle of 22°. There is evidence for interference in the form of nets, chain and rope.

The side of the sternpost is clad with planking of 40mm in thickness on the port side, the starboard side of the sternpost where it joins the outside of the transom is inaccessible. At the rear of the sternpost there appears to be a filler piece of 100mm in thickness, this is also covered with 40mm wooden sheathing. The line of the cladding on the port side and rear face of the sternpost appears to be fair, but it could merely reflect erosion. Alternatively, this may be the original height of the cladding. Across the rear face of the sternpost copper sheathing extends the full width, the measurement of the width of the sheathing is 600mm, presumably to encompass the 40mm cladding on each side of the sternpost with a good vertical corner towards the port side. The sheathing is peeling to reveal the cladding below towards the starboard side. The width of the sternpost towards the port side where it meets the outside of the transom is 600mm.

Outboard and towards the port side there are a series of thin planks (width 125mm, thickness 20mm) which are angled with their seams at 12° to the vertical. The outside faces of these planks are covered with barnacles. One of the planks close to the sternpost is missing allowing the recess to be measured (150mm, depth 20mm). A single broken plank was recovered during excavation in this area (A0011, 125mm by 20-23mm). This has tentatively been interpreted as outer hull sheathing and at first appearance looks like pine. This series of planks slopes away, downwards and towards the bow at an angle of 22°.

Beneath the sheathing and visible in plan from above is the transom structure. A series of plank tops can be seen behind the sheathing, these have a thickness of 148mm, but the joins between them are difficult to see and have not been recorded. Where observed. the joins of these are staggered with the outer hull sheathing, these appear to be square and have been interpreted as outer hull planking. Inboard of this a large curving timber (probably a transom lodging knee) meets the sternpost. This area is difficult to work due to the presence of ingots and concretions inboard and was not easily accessible and therefore not studied. The measured width of wooden elements at this point is 685mm.

Control point 1 was located on the top of the sternpost while control point 2 was placed at the junction between the structure around the sternpost (the transom) and what is interpreted as the port side (Gawronski and Kist 82, Van der Horst, 88).

Excavation followed the outer sheathing to the junction with the port side. The sheathing was observed at the top but not followed downward due to lack of time. This area had been well worked in the past. What we were concerned with was obtaining the distance between the sternpost and the junction with the port side, this was measured as 4.3m. There is no evidence for damage or tearing of timbers at this junction, the corner by CP2 appeared sound. This suggests that the least we can expect is an intact portion of the stern from the sternpost to the port side, albeit with the rudder missing. The angle of heel of the sternpost from the vertical to the port side was 33°.

The sternpost has an external width of 520mm and is racked outwards from top to bottom at an angle of 22°. There is evidence for interference in the form of nets, chain and rope.

The side of the sternpost is clad with planking of 40mm in thickness on the port side, the starboard side of the sternpost where it joins the outside of the transom is inaccessible. At the rear of the sternpost there appears to be a filler piece of 100mm in thickness, this is also covered with 40mm wooden sheathing. The line of the cladding on the port side and rear face of the sternpost appears to be fair, but it could merely reflect erosion. Alternatively, this may be the original height of the cladding. Across the rear face of the sternpost copper sheathing extends the full width, the measurement of the width of the sheathing is 600mm, presumably to encompass the 40mm cladding on each side of the sternpost with a good vertical corner towards the port side. The sheathing is peeling to reveal the cladding below towards the starboard side. The width of the sternpost towards the port side where it meets the outside of the transom is 600mm.

Outboard and towards the port side there are a series of thin planks (width 125mm, thickness 20mm) which are angled with their seams at 12° to the vertical. The outside faces of these planks are covered with barnacles. One of the planks close to the sternpost is missing allowing the recess to be measured (150mm, depth 20mm). A single broken plank was recovered during excavation in this area (A0011, 125mm by 20-23mm). This has tentatively been interpreted as outer hull sheathing and at first appearance looks like pine. This series of planks slopes away, downwards and towards the bow at an angle of 22°.

Beneath the sheathing and visible in plan from above is the transom structure. A series of plank tops can be seen behind the sheathing, these have a thickness of 148mm, but the joins between them are difficult to see and have not been recorded. Where observed. the joins of these are staggered with the outer hull sheathing, these appear to be square and have been interpreted as outer hull planking. Inboard of this a large curving timber (probably a transom lodging knee) meets the sternpost. This area is difficult to work due to the presence of ingots and concretions inboard and was not easily accessible and therefore not studied. The measured width of wooden elements at this point is 685mm.

Control point 1 was located on the top of the sternpost while control point 2 was placed at the junction between the structure around the sternpost (the transom) and what is interpreted as the port side (Gawronski and Kist 82, Van der Horst, 88).

Excavation followed the outer sheathing to the junction with the port side. The sheathing was observed at the top but not followed downward due to lack of time. This area had been well worked in the past. What we were concerned with was obtaining the distance between the sternpost and the junction with the port side, this was measured as 4.3m. There is no evidence for damage or tearing of timbers at this junction, the corner by CP2 appeared sound. This suggests that the least we can expect is an intact portion of the stern from the sternpost to the port side, albeit with the rudder missing. The angle of heel of the sternpost from the vertical to the port side was 33°.

Stratigraphy

Introduction

It was anticipated that previous excavations would have disturbed the stratigraphy outside the stern. As the most prominent feature on the seabed, we also expected it to be a catchment area for modern debris, especially fishing equipment. This was found to be the case, with nets, chain and rope tangled around the sternpost. These increased towards the starboard side and covered an area extending 3 metres away from the structure to the northwest.

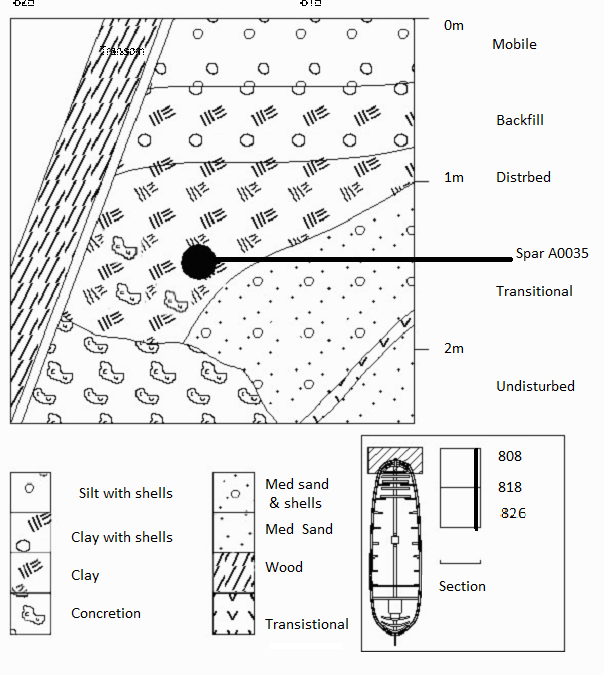

The stratigraphy outside the structure at the stern is shown in Figure 10. The first 550mm consisted of recently deposited soft silt with lots of razor shells. This gave way to clay with shells and then clay with an increasing number of concretions. This layer contained modern contaminants including toothpaste tube, plastics, and debris from previous excavations together with usually incomplete wreck derived material, especially broken bricks and glass and the enigmatic lead rolls. These recently deposited silts were easily removed. These are sediments which have infilled the site since previous excavations, basically backfill and modern mobile sediments. Also contained within these sediments were broken structural elements, outer sheathing (A0011) and a number of unidentified planks (A0009, A0010, A0012, A0027) and broken pipe bowls and stems and musket shot.

Several barrel portions including staves and part of a base were also recovered, but not all from the same container (A0014, A0015, A0016 and A0020). At 1.50m below seabed level a wooden pole (circumference 500-600mm, length 4670mm) lay across the entire trench, originating nearly at the junction with the port side (CP2). Two scaffold poles were encountered at the same level that consisted of slightly more consolidated light grey clay. This was securely embedded into a sandy deposit towards the northwest. This appeared to be spar like. A second similar but smaller object lay beneath this in a north south orientation. These marked the level of previous excavations.

The spars overlay numerous concretions, many of which seem to have consolidated into a large amorphous mass (Feature two) This originated at the port side junction, below CP2, and disappeared under the ship at this point. Amongst the mass were smaller concretions, many containing remnants of glass bottles, clay pipes, or merely the casts of these. One of these contained a pewter cup (A0036, Photo 15) that had rose and crown mark on its base. One of these appeared to contain bars (A0044), concreted blades (A0067) and knife handles (A0041).

Concreted lead rolls were also recovered, suggesting that some at least were contemporary with the wreck. The matrix within which the concretions lay was predominantly sand, but still containing razor shells albeit less numerous. Broken wood was also encountered. As the depth increased, more complete glass bottles were recovered (A0043), similarly the amount of clay increased so in one area 122 portions were recovered from one dive (00470). Boxes of pipes had been recovered from the port side during previous excavations and it is not impossible that objects such as pipes and knives had originally been contained in boxes.

At a depth of 2.5 m below seabed level the concretions became so numerous that we could not excavate between them and would have had to resort to breaking them up. To loosen these, it would have been necessary to undermine them from the north and the east and this was felt to be inappropriate. The concretions left were unbroken and solid, without any protruding organic objects. They form a naturally hard layer and it was felt that these should be left, protecting any organic material that may lie beneath.

The stratigraphy outside the structure at the stern is shown in Figure 10. The first 550mm consisted of recently deposited soft silt with lots of razor shells. This gave way to clay with shells and then clay with an increasing number of concretions. This layer contained modern contaminants including toothpaste tube, plastics, and debris from previous excavations together with usually incomplete wreck derived material, especially broken bricks and glass and the enigmatic lead rolls. These recently deposited silts were easily removed. These are sediments which have infilled the site since previous excavations, basically backfill and modern mobile sediments. Also contained within these sediments were broken structural elements, outer sheathing (A0011) and a number of unidentified planks (A0009, A0010, A0012, A0027) and broken pipe bowls and stems and musket shot.

Several barrel portions including staves and part of a base were also recovered, but not all from the same container (A0014, A0015, A0016 and A0020). At 1.50m below seabed level a wooden pole (circumference 500-600mm, length 4670mm) lay across the entire trench, originating nearly at the junction with the port side (CP2). Two scaffold poles were encountered at the same level that consisted of slightly more consolidated light grey clay. This was securely embedded into a sandy deposit towards the northwest. This appeared to be spar like. A second similar but smaller object lay beneath this in a north south orientation. These marked the level of previous excavations.

The spars overlay numerous concretions, many of which seem to have consolidated into a large amorphous mass (Feature two) This originated at the port side junction, below CP2, and disappeared under the ship at this point. Amongst the mass were smaller concretions, many containing remnants of glass bottles, clay pipes, or merely the casts of these. One of these contained a pewter cup (A0036, Photo 15) that had rose and crown mark on its base. One of these appeared to contain bars (A0044), concreted blades (A0067) and knife handles (A0041).

Concreted lead rolls were also recovered, suggesting that some at least were contemporary with the wreck. The matrix within which the concretions lay was predominantly sand, but still containing razor shells albeit less numerous. Broken wood was also encountered. As the depth increased, more complete glass bottles were recovered (A0043), similarly the amount of clay increased so in one area 122 portions were recovered from one dive (00470). Boxes of pipes had been recovered from the port side during previous excavations and it is not impossible that objects such as pipes and knives had originally been contained in boxes.

At a depth of 2.5 m below seabed level the concretions became so numerous that we could not excavate between them and would have had to resort to breaking them up. To loosen these, it would have been necessary to undermine them from the north and the east and this was felt to be inappropriate. The concretions left were unbroken and solid, without any protruding organic objects. They form a naturally hard layer and it was felt that these should be left, protecting any organic material that may lie beneath.

The stratigraphy outboard can be described as:

• Backfill and mobile modern sediments

• Transitional- the break up of the vessel and contents

• Undisturbed sediments – sand constituting 18th century seabed

Recording in the re-deposited layers outboard

The recording of objects from the disturbed infill layers outboard of the stern was different from any of the areas worked inboard. During the excavation of the overburden incomplete and unrecognizable objects were divided by material type and stored as recommended under dive number. If the object was recognizable and relatively complete (such as lead shot A0002) it was registered as an object and fully recorded in a specifically created database. Photographs of artefacts entered into the recording system were taken for identification purposes immediately with a digital camera and accessed to the artefact file. Modern objects were discarded while all others were kept. Objects such as incomplete pipe stems and bottle fragments were kept separately under dive number, but not individually registered. If these bulk recovered objects are processed ashore, they can be added to the finds register, similarly any concretions opened during conservation can be added.

The vast number of broken glass bottle fragments and a lot of the bricks encountered in the disturbed levels (above 1.50m) is confusing, these must have washed in from elsewhere or possibly discarded following previous excavations.

• Backfill and mobile modern sediments

• Transitional- the break up of the vessel and contents

• Undisturbed sediments – sand constituting 18th century seabed

Recording in the re-deposited layers outboard

The recording of objects from the disturbed infill layers outboard of the stern was different from any of the areas worked inboard. During the excavation of the overburden incomplete and unrecognizable objects were divided by material type and stored as recommended under dive number. If the object was recognizable and relatively complete (such as lead shot A0002) it was registered as an object and fully recorded in a specifically created database. Photographs of artefacts entered into the recording system were taken for identification purposes immediately with a digital camera and accessed to the artefact file. Modern objects were discarded while all others were kept. Objects such as incomplete pipe stems and bottle fragments were kept separately under dive number, but not individually registered. If these bulk recovered objects are processed ashore, they can be added to the finds register, similarly any concretions opened during conservation can be added.

The vast number of broken glass bottle fragments and a lot of the bricks encountered in the disturbed levels (above 1.50m) is confusing, these must have washed in from elsewhere or possibly discarded following previous excavations.

Finds

Introduction

A total of 69 numbers were allocated to finds in trench one, this is in addition to the bulk lifted items under dive number. Details about registered artefacts are in Appendix 1.

Those listed below do not include bulk lifted objects that may produce further artefacts upon processing, these included wine and Geneva bottles, clay pipes, bricks, and lead rolls. The lead rolls are interesting as they occur both in disturbed and in undisturbed levels inboard and outboard. The rolls are of different sizes and are simply made by overlapping or merely gripping together a small lead patch to form a roll. Some of these still retained rope within as if they gripped the rope. It is suggested that these are weights for fishing nets, some new and some contemporary with the sinking. The finding of several within a concretion containing glass and Geneva bottles lends strength to this theory. There are a number of different sizes and some are initialed. Although bulk lifted, none were individually registered from Trench 1.

All objects derived from a large concretion that began close to the port side beneath CP2 and filled much of the bottom of the trench were noted as such. This was given a feature number, Feature 1. As all items were concreted together it was thought that they may have derived from a container of some sort and should be treated in the first instance as belonging together.

The types of objects recovered from Trench 1 include the following:

Bricks

There is a slight variation in size, with examples between 220mm and 225mm in length, 100mm105mm in width and 40mm-45mm in thickness (A0001, A0003, A0007, A0013, A0018, A0067, A0069).

The majority of these bricks were in the disturbed levels and just below so they must either be derived from previous excavation discard or from the bricks in store in the hold. As they are not generally stored this far astern their presence may suggest a stern down attitude for the hull. Alternatively, human activity in the form of trawling over the cargo hold towards the North may have redistributed them.

Barrel elements

Several elements from barrels were recovered from within the grey clay layer. This included staves (0014,0015,0039,0055) and base fragment 0037,14,20) and hoop fragment 0015,0016.

Glass bottles

The majority of broken bottles were onion shaped wine bottles but some square Geneva bottles were noted. The bulk of glass was recovered within the disturbed upper levels, but within and below the concretions (1.6m-2.5m) negative casts of complete bottles were recovered. Several nearly complete examples were found within the sand level along with some with corks and copper alloy wire (A0005, A0043, A0068 Geneva, A0065).

Ordnance

Two small lead shot were recovered 17mm (A0002), 15mm (A0028) and a concretion containing what may be decomposing bar shot with 10mm bar (A0044).

Pipe Fragments

Fragments from the disturbed upper sediments were broken and stem fragments were given the dive number. A number of heel marks[6] were noted on the pipes recovered from beneath the spar. These marks included the initials WS (A0008, A0017, A0021, A0047), Crown over 7 (A0022, A0041), an arch (A0045, A0041) and a portcullis (A0041, like Hollandia 18). None of the bowls showed signs of burning so they were probably being transported rather than in use. A study of the distribution and frequency of pipes bearing particular marks combined with whether they were used or unused should reflect bulk orders from one pipe maker and individual pipes in use (A0023 (1-15), A0038 (1-41)).

Knife Handles

Several wooden knife handles with a geometric incised pattern were recovered from close to CP2, (A0024) with ferule (A0025, A0041). An unidentified tool handle was also recovered (A0052).

Furniture

A decorated wooden frame of some sort may represent furniture (A0059). Carved furniture would have been used in the stern cabins on the upper and quarter decks.

Ceramics

There were broken elements of stoneware and china, all within the pockets of sand around the concretions. These included some china saucer fragments (A0049, A0050) a glazed pot (A0058) and fragments (A0060, A0061, A0063, A0064).

Pewter

One small pewter cup bearing a rose and crown mark on its base was recovered just beneath the spar, resting on and concreted to the large concretion (Feature 2). This had a height of 100mm, base diameter of 73mm and mouth of 86mm.

Specie

Two ducatons were recovered (A0048) while other concretions may contain corroded silver coinage.

Ship’s Structure

A number of elements of superstructure were recovered, some from the backfill levels (A0009 1610mm x 840mm x 150mm), this had square holes of 8mm x 8mm with animal hair and glue on one face and is similar to A0030. Another piece of structure in the backfill was thinner, of 28mm thick and 65mm wide with numerous nail holes. This is often found when two pieces of thinner wood are attached together with nails to give a thicker element. An outer hull sheathing plank was found (A0011 530 mm x 125mm x 22 mm), this may well be the plank which was missing next to the sternpost. Other structural fragments include A0012 and A0027.

The large spar exposed during previous excavations was recovered, this had a length of 4670mm and circumference of 640mm but included 11 holes, not all of which penetrated the spar. The condition is good with the exception of the end that had been deeply buried in the sandbank at the northwest corner of the trench, as this appeared gribbled. Stratigraphically it is in a backfilled area and cannot be proven to be wreck derived by location.

Miscellaneous fragments included a slat, possibly the remains of a box (A0026, A0056 and A0040) and a wooden block (A0054).

Environmental

A number of samples were taken for analysis (A0004, A0033 and A0034) and a substance resembling yellow amber was collected (A0062).

Discrete concretions were recovered, these included some (A0031, A0032) directly below CP2 and possibly a blade fragment (A0066).

The excavation of a corroded scaffold screw with a 5mm coating of concretion over all of it provides an interesting indicator of the speed of concretion build up in Trench 1 as the screw was deposited between 1989 and 1993.

Many items are concreted in a grey / black granular concretion suggestive of gunpowder, analysis may confirm this hypothesis.

Those listed below do not include bulk lifted objects that may produce further artefacts upon processing, these included wine and Geneva bottles, clay pipes, bricks, and lead rolls. The lead rolls are interesting as they occur both in disturbed and in undisturbed levels inboard and outboard. The rolls are of different sizes and are simply made by overlapping or merely gripping together a small lead patch to form a roll. Some of these still retained rope within as if they gripped the rope. It is suggested that these are weights for fishing nets, some new and some contemporary with the sinking. The finding of several within a concretion containing glass and Geneva bottles lends strength to this theory. There are a number of different sizes and some are initialed. Although bulk lifted, none were individually registered from Trench 1.

All objects derived from a large concretion that began close to the port side beneath CP2 and filled much of the bottom of the trench were noted as such. This was given a feature number, Feature 1. As all items were concreted together it was thought that they may have derived from a container of some sort and should be treated in the first instance as belonging together.

The types of objects recovered from Trench 1 include the following:

Bricks

There is a slight variation in size, with examples between 220mm and 225mm in length, 100mm105mm in width and 40mm-45mm in thickness (A0001, A0003, A0007, A0013, A0018, A0067, A0069).

The majority of these bricks were in the disturbed levels and just below so they must either be derived from previous excavation discard or from the bricks in store in the hold. As they are not generally stored this far astern their presence may suggest a stern down attitude for the hull. Alternatively, human activity in the form of trawling over the cargo hold towards the North may have redistributed them.

Barrel elements

Several elements from barrels were recovered from within the grey clay layer. This included staves (0014,0015,0039,0055) and base fragment 0037,14,20) and hoop fragment 0015,0016.

Glass bottles

The majority of broken bottles were onion shaped wine bottles but some square Geneva bottles were noted. The bulk of glass was recovered within the disturbed upper levels, but within and below the concretions (1.6m-2.5m) negative casts of complete bottles were recovered. Several nearly complete examples were found within the sand level along with some with corks and copper alloy wire (A0005, A0043, A0068 Geneva, A0065).

Ordnance

Two small lead shot were recovered 17mm (A0002), 15mm (A0028) and a concretion containing what may be decomposing bar shot with 10mm bar (A0044).

Pipe Fragments

Fragments from the disturbed upper sediments were broken and stem fragments were given the dive number. A number of heel marks[6] were noted on the pipes recovered from beneath the spar. These marks included the initials WS (A0008, A0017, A0021, A0047), Crown over 7 (A0022, A0041), an arch (A0045, A0041) and a portcullis (A0041, like Hollandia 18). None of the bowls showed signs of burning so they were probably being transported rather than in use. A study of the distribution and frequency of pipes bearing particular marks combined with whether they were used or unused should reflect bulk orders from one pipe maker and individual pipes in use (A0023 (1-15), A0038 (1-41)).

Knife Handles

Several wooden knife handles with a geometric incised pattern were recovered from close to CP2, (A0024) with ferule (A0025, A0041). An unidentified tool handle was also recovered (A0052).

Furniture

A decorated wooden frame of some sort may represent furniture (A0059). Carved furniture would have been used in the stern cabins on the upper and quarter decks.

Ceramics

There were broken elements of stoneware and china, all within the pockets of sand around the concretions. These included some china saucer fragments (A0049, A0050) a glazed pot (A0058) and fragments (A0060, A0061, A0063, A0064).

Pewter

One small pewter cup bearing a rose and crown mark on its base was recovered just beneath the spar, resting on and concreted to the large concretion (Feature 2). This had a height of 100mm, base diameter of 73mm and mouth of 86mm.

Specie

Two ducatons were recovered (A0048) while other concretions may contain corroded silver coinage.

Ship’s Structure

A number of elements of superstructure were recovered, some from the backfill levels (A0009 1610mm x 840mm x 150mm), this had square holes of 8mm x 8mm with animal hair and glue on one face and is similar to A0030. Another piece of structure in the backfill was thinner, of 28mm thick and 65mm wide with numerous nail holes. This is often found when two pieces of thinner wood are attached together with nails to give a thicker element. An outer hull sheathing plank was found (A0011 530 mm x 125mm x 22 mm), this may well be the plank which was missing next to the sternpost. Other structural fragments include A0012 and A0027.

The large spar exposed during previous excavations was recovered, this had a length of 4670mm and circumference of 640mm but included 11 holes, not all of which penetrated the spar. The condition is good with the exception of the end that had been deeply buried in the sandbank at the northwest corner of the trench, as this appeared gribbled. Stratigraphically it is in a backfilled area and cannot be proven to be wreck derived by location.

Miscellaneous fragments included a slat, possibly the remains of a box (A0026, A0056 and A0040) and a wooden block (A0054).

Environmental

A number of samples were taken for analysis (A0004, A0033 and A0034) and a substance resembling yellow amber was collected (A0062).

Discrete concretions were recovered, these included some (A0031, A0032) directly below CP2 and possibly a blade fragment (A0066).

The excavation of a corroded scaffold screw with a 5mm coating of concretion over all of it provides an interesting indicator of the speed of concretion build up in Trench 1 as the screw was deposited between 1989 and 1993.

Many items are concreted in a grey / black granular concretion suggestive of gunpowder, analysis may confirm this hypothesis.

Structure Trench 2

Structural Survey

The positions of the first dive in trench 2 placed us within the vessel 2m east of the transom and 1214m to the south[15], assuming that the stern section was not out of line or twisted away from the rest of the vessel. Exploration of the surrounding area suggested nothing visible to the west except bricks with wooden structural elements visible to the east. Excavation in the first instance was confined to the brick feature and trying to locate an intact portion of port side hull structure, a sandwich formed of inner hull planking or ceiling planking, frames, outer planking and sacrificial sheathing.

Structural Indicators

Control points were placed on the major items of structure, with the exception of CP3, a large roll of lead within grid B8B.

A substantial longitudinal beam (CP8 to south, 11 on middle and 12 on north end) may be a longitudinal deck support or a stringer for the port side. The beam is 120mm x 120mm but is broken at two nail positions 140mm apart so it may have been wider or thicker, this lies at 330° and has a length of three metres. At its north end stored barrel ends were found. To the west of this a similar size longitudinal beam was found and a point was put on its southern, broken end (CP10).

A second substantial element was a carling was found with five slots for half beams, four of which were present. The carling was also aligned at 330° and had a width of 90mm, a depth of 140mm and a length of 2896mm. The spacing of the half beams varied, one with only 80mm and one up to 200mm. Two of these half beams had compass bearings measured at 235° and 240°. The slots varied between 80mm and 100. CP7 was placed on the broken southern end. At the north end where it disappeared into the sediment and jumble of timber, including deck planks of 50mm in thickness and between 170mm and 200mm wide. This is undoubtedly a deck support structure, or some form of half deck support structure. The most unusual feature of this is that the half beams are rebated into the western face of the timber. If this represents an intact structural element, the fair face of the timber should represent the side of a hatch (hence no half beams). The timber is too close to the position of the port side for a hatch, unless it has slipped dramatically towards the port side. The other possibility is that the eastern (non-rebated) edge lay on a stringer against the port side, and was not itself a beam shelf, in which case it is nearly a metre west of where the port side should be. The other possibility is that it is upside down. It would appear that this is an isolated portion of deck support, further excavation to the north dislodged it and the half beams became loose and displaced during the excavation.

The other substantial timbers were associated with a longitudinal heavy timber, marked CP4 on its southern, torn end. The timber was oriented at angle of 340° and had a width of 450mm and thickness of 100mm and it rested on broken wooden planks. This could be a stringer on the inside of the hull or an outer hull plank.

Above and behind CP4 were a number of thinner smaller planks that could be outer hull sheathing. Nearly meeting this timber was a curved element CP5 which was 250mm x 220mm, this looks like the top of a rider or large internal floor timber but could also be a portion of a rib with the planking displaced.

Although there were a number of elements of structure that were identified, the port side of the vessel in a coherent form was never found. For this reason, an excavation to the east or outboard of the projected line of the hull (trench 3) was undertaken to see whether the hull was detached and had collapsed to the east and to assess the nature of the stratigraphy, and the artefact assemblage. Several areas were tested, with excavations in the north outboard of CP9 (W4A, W4B) during dives 88-92. Areas W5A and W6A in dives 95, 96, 123 and 124 and a number of dives in W8A (120,121,126,128).

The positions of the first dive in trench 2 placed us within the vessel 2m east of the transom and 1214m to the south[15], assuming that the stern section was not out of line or twisted away from the rest of the vessel. Exploration of the surrounding area suggested nothing visible to the west except bricks with wooden structural elements visible to the east. Excavation in the first instance was confined to the brick feature and trying to locate an intact portion of port side hull structure, a sandwich formed of inner hull planking or ceiling planking, frames, outer planking and sacrificial sheathing.

Structural Indicators

Control points were placed on the major items of structure, with the exception of CP3, a large roll of lead within grid B8B.

A substantial longitudinal beam (CP8 to south, 11 on middle and 12 on north end) may be a longitudinal deck support or a stringer for the port side. The beam is 120mm x 120mm but is broken at two nail positions 140mm apart so it may have been wider or thicker, this lies at 330° and has a length of three metres. At its north end stored barrel ends were found. To the west of this a similar size longitudinal beam was found and a point was put on its southern, broken end (CP10).

A second substantial element was a carling was found with five slots for half beams, four of which were present. The carling was also aligned at 330° and had a width of 90mm, a depth of 140mm and a length of 2896mm. The spacing of the half beams varied, one with only 80mm and one up to 200mm. Two of these half beams had compass bearings measured at 235° and 240°. The slots varied between 80mm and 100. CP7 was placed on the broken southern end. At the north end where it disappeared into the sediment and jumble of timber, including deck planks of 50mm in thickness and between 170mm and 200mm wide. This is undoubtedly a deck support structure, or some form of half deck support structure. The most unusual feature of this is that the half beams are rebated into the western face of the timber. If this represents an intact structural element, the fair face of the timber should represent the side of a hatch (hence no half beams). The timber is too close to the position of the port side for a hatch, unless it has slipped dramatically towards the port side. The other possibility is that the eastern (non-rebated) edge lay on a stringer against the port side, and was not itself a beam shelf, in which case it is nearly a metre west of where the port side should be. The other possibility is that it is upside down. It would appear that this is an isolated portion of deck support, further excavation to the north dislodged it and the half beams became loose and displaced during the excavation.

The other substantial timbers were associated with a longitudinal heavy timber, marked CP4 on its southern, torn end. The timber was oriented at angle of 340° and had a width of 450mm and thickness of 100mm and it rested on broken wooden planks. This could be a stringer on the inside of the hull or an outer hull plank.

Above and behind CP4 were a number of thinner smaller planks that could be outer hull sheathing. Nearly meeting this timber was a curved element CP5 which was 250mm x 220mm, this looks like the top of a rider or large internal floor timber but could also be a portion of a rib with the planking displaced.

Although there were a number of elements of structure that were identified, the port side of the vessel in a coherent form was never found. For this reason, an excavation to the east or outboard of the projected line of the hull (trench 3) was undertaken to see whether the hull was detached and had collapsed to the east and to assess the nature of the stratigraphy, and the artefact assemblage. Several areas were tested, with excavations in the north outboard of CP9 (W4A, W4B) during dives 88-92. Areas W5A and W6A in dives 95, 96, 123 and 124 and a number of dives in W8A (120,121,126,128).

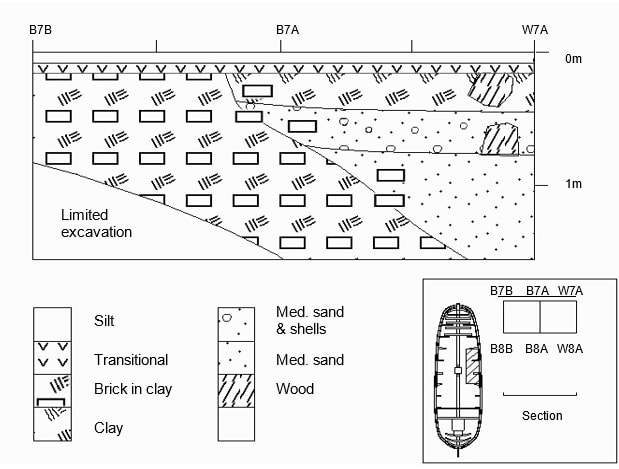

Stratigraphy Trench 2

Towards the starboard side the bricks were visible on the surface covered with only a light dusting of grey silt. The sediments between the bricks was a white buttery silt, possibly representing deposition within the hull of suspended sediment as the vessel was still a coherent structure.

Towards the port side the sediment was deeper, with mobile silt overlying 300mm of dark grey clay (A0200) which peeled off easily to a thin (200mm) loose layer of broken shells in sand, predominantly razor shells (A0201). This shelly layer may be seabed deposit formed when the upper structure had deteriorated, and the seabed became flat. Beneath this the bricks were stored within buttery silt which was noted by all divers as being cold to touch. Artefacts were within the brick silt/clay layer, Figure 11. Around the more scattered bricks on the east the sediment was white clay with sand contained within it, the bricks were too deeply stored on the west. The amount of sand increased towards the east. Excavations into this layer resulted in many objects although few of these seemed to be bulk cargo objects[17] but either personal objects in use or for use within the ship (buckles, spoon, lead sheets (A0406, A0407).

Features allocated within trench 2 and the explored area around it included the following:

Feature 1 – ROV survey of what appeared to be of a brick structure rather than stored bricks. Feature 3 - Stored bricks

Feature 4 – Cylindrical object

Feature 5 – White casts which appeared to contain concreted remains of what was in barrels resting on bricks.

Features allocated within trench 2 and the explored area around it included the following:

Feature 1 – ROV survey of what appeared to be of a brick structure rather than stored bricks. Feature 3 - Stored bricks

Feature 4 – Cylindrical object

Feature 5 – White casts which appeared to contain concreted remains of what was in barrels resting on bricks.

Structural Indicators Trench 3

Although few structural elements were found within any of the areas designated as outboard, a loose knee (A0518) and rigging block (A0519) were recovered. These elements were mixed with nearly complete china cups (A0540, A0505) and lead rolls (AO490, 1-11).

The concreted columns excavated in areas W5A and W8A do suggest that the sand area represents the sediments outside the ship, with the columns being the migration of the iron heads of the hull bolts into the sand. It is possible that the broken elements noted in trench 2 are portions of the side of the vessel which are detached and lying in part to the west (CP4, CP5). The sand infill to the east of the bricks between sectors 5 and 8 combined with the lack of significant structure suggest that the vessel has broken open at this point. This does not necessarily mean that the ship has broken between the bow and stern, as the angle of the bulk of the brick cargo along its north/south axis does not appear to change. There would however appear to be damage to the port side in this area, with sand entering the vessel. This is not surprising as items of trawling gear was present in large quantities just north of CP9.

The concreted columns excavated in areas W5A and W8A do suggest that the sand area represents the sediments outside the ship, with the columns being the migration of the iron heads of the hull bolts into the sand. It is possible that the broken elements noted in trench 2 are portions of the side of the vessel which are detached and lying in part to the west (CP4, CP5). The sand infill to the east of the bricks between sectors 5 and 8 combined with the lack of significant structure suggest that the vessel has broken open at this point. This does not necessarily mean that the ship has broken between the bow and stern, as the angle of the bulk of the brick cargo along its north/south axis does not appear to change. There would however appear to be damage to the port side in this area, with sand entering the vessel. This is not surprising as items of trawling gear was present in large quantities just north of CP9.

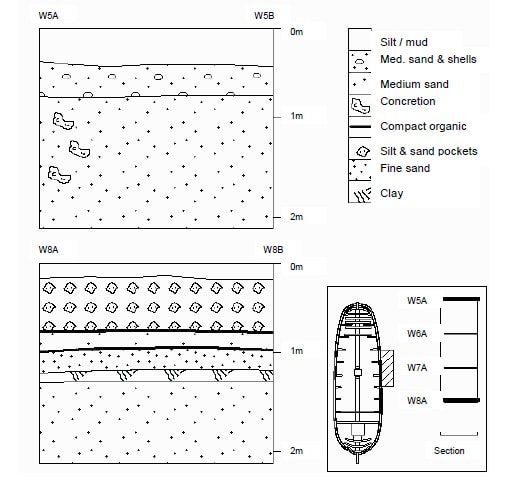

Stratigraphy Trench 3

In the north sector W5A (Figure 12, upper) there was a grey mobile silt layer of 300 mm in depth that held wreck derived material. Beneath this was a layer of broken shells in grey sand, with an increased number of finds. Beneath this, at a depth of 550mm was coarse sterile white sand with only the concreted remains of corroding ship fastenings.

In the south of trench 3, in sector W8A (Figure 12, lower), sedimentation included a fine layer of mobile grey silt of 50mm to 100mm in thickness which overlay grey mud with sand inclusions 600mm thick. The interface between this and the layer below held a dark organic layer of less than 10mm thickness. Beneath this was a compact sand layer of 120mm that overlay a thin organic layer containing shells and sand, this overlay 300mm of fine grey sand. Beneath this layer was a 50- 100mm layer of white to grey clay that overlay compact golden sand at a depth of 1170mm.

In the south of trench 3, in sector W8A (Figure 12, lower), sedimentation included a fine layer of mobile grey silt of 50mm to 100mm in thickness which overlay grey mud with sand inclusions 600mm thick. The interface between this and the layer below held a dark organic layer of less than 10mm thickness. Beneath this was a compact sand layer of 120mm that overlay a thin organic layer containing shells and sand, this overlay 300mm of fine grey sand. Beneath this layer was a 50- 100mm layer of white to grey clay that overlay compact golden sand at a depth of 1170mm.

The number of artefacts and the excellent condition of some of them suggest rapid burial and again reflect personal rather than trade items. These include a pencil (A0231, Photo 11), ducatons with a clear date of 1733 (A0217) together with groups such as 60 lead rolls of three differing sizes (A0220), six copper alloy buckles (A0223-228) together with ceramic and pipe fragments and the odd brick. The fine grey sand layer held concretions, many with stalactite formations as though they had formed on the underneath of an overhanging structure, possibly the ends of iron bolts which in time hardened the sand. The purity of the golden sand layer at 1170mm that may represent the original seabed level. The lack of finds in the layer above suggests that this was a harder clay layer that formed when the ship landed on the seabed.

Recording

All items excavated from trenches 2 and 3 were given artefact numbers and kept. Where many items of the same type such as broken bottles, lead rolls, pins and specie were excavated together they were given the same number with part numbers, for example lead rolls (A0490 1-11) and bricks

(A0420 1-350)

Finds Trenches 2 and 3

Three hundred and ninety finds were recovered from trenches 2 and 3 during 55 dives, 214 from trench 3 outboard with 183 of these from sector W8A. All of these are of a mixed nature, some personal, some ship’s equipment such as an oil lamps (Photos 21,22), pipes and taps (Photo 23) as well as the net weights (Photos 24, 25).

Trench 2, Inboard

Excavation in trench 2 included sectors B5A, B6A, B7A, B8A and further inboard, B7B, B8B. In addition, a small excavation to reveal detail of the cylindrical Feature (4) revealed a few items. All of these are listed in Appendix 1 by simple name within each sector.

The density of finds increases to the east (port side) with most types of finds being found in greater numbers outboard. One exception was in B7B, where 60 ducatons were found, with 22 on one dive (78) and 23 on another (113). Most items are of a durable nature, with inorganics most prevalent. Unusual features included the discrete pockets of fruit stones and seeds (A0360, 1-25, 0421) and bones (A0360, A0361). Dating these items might prove interesting, as it is possible that these are modern contaminants discarded during previous excavation seasons. Their incorporation within sediments yielding ducatons (A0362) and other wreck-derived objects (A0359 - A0364) is important.

The brick cargo contained a number of items within the white clay matrix around the bricks. The majority were not found in groups which one could suggest had derived from broken containers, but more as isolated individual objects. These objects appear to be more personal than cargo in nature, there were few identical objects reflective of bulk goods in transit. Items within the bricks consisted of durable individual objects such as buckles (Photo 26), buttons, cloth seals which may have derived from a cargo of cloth bales, pewter spoons (Photo 27) and ducatons, some in small groups which may have resulted from decayed purses (A0414, 1-23).

Buckles and Buttons

The eight copper alloy buckles all appear unique, and although three were uncovered in one dive (111), even these were different. The eight buttons were recovered on four separate dives (85,95,111.115).

Cloth Seals

All three cloth seals were within the bricks, two found together on one dive (85) and one in the previous (84). These items, together with the wine bottles, bricks and wood, are the only real indicators of cargo goods in trench 2. It is possible that cloth bales stored above the bricks have disintegrated leaving only the seals trapped within the bricks.

Pipes

Only 9 pipe fragments were recovered.

Specie

A single gold coin, a hand-struck ducat dated 1729 minted in Utrecht as part of the Company’s money aboard (A0402 photo centre pages).

Bottles

Only 18 numbers were allocated to bottles.

Lead Rolls

Forty-two lead rolls were recovered, the largest concentration in B7A (19).

Other items

Broken wineglass stems (Photo 28) of differing types are suggestive of items that came from decks above as did the fork (A0385), 12 spoons, 7 shoe elements. Two shot were recovered (A0410, A0417, both lead) to living quarters and working areas rather than bulk storage areas.

Trench 3, Outboard

Excavation occurred in sectors W5A-W8A/B over 11 dives. Although the distinction of inboard and outboard is difficult in the absence of coherent structure, the sediment changes suggest that the designation on of the original grid squares with “W” representing outboard and “B” representing inboard appears sound. The huge number of finds from the sector W8A alone reflect the tilt to port which has resulted in objects and structural elements from the decks above the hold being distributed outside the port side.

Outside the expected line of the port side pockets of silt mixed with sand yielded clusters of objects (A0580, A0592). All of these pockets produced mixed items, for example structural elements (A0581), sheathing, blocks (A0575, A0568), gland (A0566), rigging (A0583) and a hollow wood cylinder (A0586). Items included (dive 119) a musket (A0548) a trigger guard (A0508), an oil lamp (A0507) and a tap (A0465) along with broken glass stems, pottery, lead rolls and a shoe (A0439).

Buckles and buttons

Twelve copper alloy buckles were recovered, most from sector W8A. Although some were found together, they do not appear to be identical. The distribution for the eight buttons is similar.

Cloth Seals

No cloth seals were recovered.

Pipes

Only eight pipe fragments were found outboard ,one of which was a bowl (A0483).

Bottles

Eighteen numbers were allocated to bottles or parts of bottles (Photo 29).

Other.

It is from this sector that some of the most interesting artefacts derive. This includes the two oil lamps, one that may have been in use on the gun deck, fittings such as taps, hinges and rigged elements of rigging. As well as these items, tools, ceramics (22 listed) in the form of both stoneware and china were recovered. Sector W8A also yielded the brass capped pencil (A0231), musket and guard29. A fine VOC sash buckle was found in sector W7A (A0254, Photo centre page).

Lead rolls.

One hundred and seventy-two lead rolls were found outboard. Sector W8A alone yielded 98, with a further 57 between W8A and W8B. A further 36 were found on the border of B8A and W8A. Undoubtedly some are contemporary with the wreck, others may be later evidence of fishing on the site. Some bear initials, and some still retain rope and others not – despite seemingly identical burial conditions. Both these features at present appear random. They are found in a variety of sizes, often together. It is hard to tell whether some represent nets in transit, or in use during the voyage and others merely lead rolls for manufacturing nets in Batavia. They are cylinders, it would be easier to transport flat lead pieces.

Recording

All items excavated from trenches 2 and 3 were given artefact numbers and kept. Where many items of the same type such as broken bottles, lead rolls, pins and specie were excavated together they were given the same number with part numbers, for example lead rolls (A0490 1-11) and bricks

(A0420 1-350)

Finds Trenches 2 and 3

Three hundred and ninety finds were recovered from trenches 2 and 3 during 55 dives, 214 from trench 3 outboard with 183 of these from sector W8A. All of these are of a mixed nature, some personal, some ship’s equipment such as an oil lamps (Photos 21,22), pipes and taps (Photo 23) as well as the net weights (Photos 24, 25).

Trench 2, Inboard

Excavation in trench 2 included sectors B5A, B6A, B7A, B8A and further inboard, B7B, B8B. In addition, a small excavation to reveal detail of the cylindrical Feature (4) revealed a few items. All of these are listed in Appendix 1 by simple name within each sector.

The density of finds increases to the east (port side) with most types of finds being found in greater numbers outboard. One exception was in B7B, where 60 ducatons were found, with 22 on one dive (78) and 23 on another (113). Most items are of a durable nature, with inorganics most prevalent. Unusual features included the discrete pockets of fruit stones and seeds (A0360, 1-25, 0421) and bones (A0360, A0361). Dating these items might prove interesting, as it is possible that these are modern contaminants discarded during previous excavation seasons. Their incorporation within sediments yielding ducatons (A0362) and other wreck-derived objects (A0359 - A0364) is important.

The brick cargo contained a number of items within the white clay matrix around the bricks. The majority were not found in groups which one could suggest had derived from broken containers, but more as isolated individual objects. These objects appear to be more personal than cargo in nature, there were few identical objects reflective of bulk goods in transit. Items within the bricks consisted of durable individual objects such as buckles (Photo 26), buttons, cloth seals which may have derived from a cargo of cloth bales, pewter spoons (Photo 27) and ducatons, some in small groups which may have resulted from decayed purses (A0414, 1-23).

Buckles and Buttons

The eight copper alloy buckles all appear unique, and although three were uncovered in one dive (111), even these were different. The eight buttons were recovered on four separate dives (85,95,111.115).

Cloth Seals

All three cloth seals were within the bricks, two found together on one dive (85) and one in the previous (84). These items, together with the wine bottles, bricks and wood, are the only real indicators of cargo goods in trench 2. It is possible that cloth bales stored above the bricks have disintegrated leaving only the seals trapped within the bricks.

Pipes

Only 9 pipe fragments were recovered.

Specie

A single gold coin, a hand-struck ducat dated 1729 minted in Utrecht as part of the Company’s money aboard (A0402 photo centre pages).

Bottles

Only 18 numbers were allocated to bottles.

Lead Rolls

Forty-two lead rolls were recovered, the largest concentration in B7A (19).

Other items

Broken wineglass stems (Photo 28) of differing types are suggestive of items that came from decks above as did the fork (A0385), 12 spoons, 7 shoe elements. Two shot were recovered (A0410, A0417, both lead) to living quarters and working areas rather than bulk storage areas.

Trench 3, Outboard

Excavation occurred in sectors W5A-W8A/B over 11 dives. Although the distinction of inboard and outboard is difficult in the absence of coherent structure, the sediment changes suggest that the designation on of the original grid squares with “W” representing outboard and “B” representing inboard appears sound. The huge number of finds from the sector W8A alone reflect the tilt to port which has resulted in objects and structural elements from the decks above the hold being distributed outside the port side.

Outside the expected line of the port side pockets of silt mixed with sand yielded clusters of objects (A0580, A0592). All of these pockets produced mixed items, for example structural elements (A0581), sheathing, blocks (A0575, A0568), gland (A0566), rigging (A0583) and a hollow wood cylinder (A0586). Items included (dive 119) a musket (A0548) a trigger guard (A0508), an oil lamp (A0507) and a tap (A0465) along with broken glass stems, pottery, lead rolls and a shoe (A0439).

Buckles and buttons

Twelve copper alloy buckles were recovered, most from sector W8A. Although some were found together, they do not appear to be identical. The distribution for the eight buttons is similar.

Cloth Seals

No cloth seals were recovered.

Pipes

Only eight pipe fragments were found outboard ,one of which was a bowl (A0483).

Bottles

Eighteen numbers were allocated to bottles or parts of bottles (Photo 29).

Other.

It is from this sector that some of the most interesting artefacts derive. This includes the two oil lamps, one that may have been in use on the gun deck, fittings such as taps, hinges and rigged elements of rigging. As well as these items, tools, ceramics (22 listed) in the form of both stoneware and china were recovered. Sector W8A also yielded the brass capped pencil (A0231), musket and guard29. A fine VOC sash buckle was found in sector W7A (A0254, Photo centre page).

Lead rolls.

One hundred and seventy-two lead rolls were found outboard. Sector W8A alone yielded 98, with a further 57 between W8A and W8B. A further 36 were found on the border of B8A and W8A. Undoubtedly some are contemporary with the wreck, others may be later evidence of fishing on the site. Some bear initials, and some still retain rope and others not – despite seemingly identical burial conditions. Both these features at present appear random. They are found in a variety of sizes, often together. It is hard to tell whether some represent nets in transit, or in use during the voyage and others merely lead rolls for manufacturing nets in Batavia. They are cylinders, it would be easier to transport flat lead pieces.

Passive Holding of Finds

Holding facilities were prepared in order to provide conditions to inhibit further physical, biological or chemical deterioration of the artefacts.

Following registration, documentation and photography, all finds were stored for transport to the conservation facility at the Stedelijk Museum in Vlissingen. Under the direction of the conservator Ton van der Horst, intervention was kept to a minimum and the storage medium chosen was based on material type.

Cleaning was reduced to what was required for identification, measuring and photography and undertaken with a soft bristle brush. Any artefact with a residue which was presumed to be organic in nature, whether on the outside surface (paint, textile) or on the inside (packaging, organic contents) was not washed, but heat sealed within polythene or sealed within a strong zip polythene bag.

• All metals, ceramics and stone were stored in saltwater

• Wood, leather, bone or horn was sealed in polythene within a limited amount of seawater

• Textile and organic material was not re-immersed, but kept damp and sealed

The storage areas were located about the vessel in numbered tanks, all were within darkened areas and the large seawater tank was insulated. Where support was required, small containers with saturated foam were utilized.

Conservation

Ton Van der Horst

Procedure

As soon as the vessel docked all finds were transported to the conservation facility at the Stedelijk Museum in Vlissingen. They are cleaned and separated into material types before conservation. Any unphotographed artefacts are photographed. Anything missing from the artefact registration form is added at this stage.

Wood and leather are placed immediately into a large freezer, or tank containing fresh water if they are too large for the freezers. Once the organics have been frozen, water is removed by placing them in a vacuum freeze-drying chamber (Edwards BF 4) which can extract 1.2 kg of ice in 12 hours. After freeze-drying, wooden artefacts are treated with linseed oil to prevent any further drying or collapse. Leather is freeze-dried, but a specific leather dressing is applied once they are dry. If possible, reconstruction is undertaken at this stage.

Both complete and incomplete wine bottles are washed in tap water, as are all glass artefacts. This is undertaken within a circulation tank where the water is filtered. Routine readings for chlorides are taken. When the reading is stable, suggesting that there are no more chlorides within the glass, the artefacts are washed in distilled water until the chloride reading is less than 20 parts per million. The glass is then dried and immersed into a 1/10 solution of Dormoplast SG Normal that provides a coating. Any corks are treated with a two-part glue to prevent shrinkage.

Earthenware, stoneware and porcelain are washed in distilled water and dried. After each excavation season all the fragments from each trench are gathered together to try and piece together any vessels.

Bronze, silver, copper, brass and pewter are cleaned in an electrolytic tank using a 5% sodium hydroxide solution with the object forming the anode attached to a stainless-steel cathode. A 5 volt electrical supply is used. Following electrolytic reduction, the objects are neutralised and cleaned ultrasonically at between 40 - 70 degrees centigrade by turning a power supply on an off in intervals of not longer than five minutes. This short interval is necessary to prevent cavitation occurring which could damage the object. After the object is dry it is lacquered with Pantarol.

Gold is cleaned in an 85% solution of nitric acid, neutralised, ultrasonically cleaned and dried.

Steel and cast iron are treated by immersion in a 63 gram per litre solution of sodium sulphite which is covered and heated to 70 degrees celcius and constantly mixed. The solution is changed weekly following routine chloride readings. Once the readings remain below 100 parts per million, the objects are considered stable. The remaining chlorides have changed into barium sulphate. The object is then dried and placed in melted microcrystalline wax.

Reconstruction

All incomplete objects are studied with their associated objects. Any broken objects which can be reconstructed are put together. Objects which have been damaged or bent such as pewter plates are carefully reconstructed to show their original form and placed on display to tell their own story. Photo 37 shows reconstructed lanterns from previous excavations and a conserved oil lamp from the 2000 season.

Project Statistics

Mark Fuller

Tidal ConditionsA set of tidal roses for the area surrounding the Vliegent Hart site based on the standard port of Vlissingen, Netherlands, were used to predict the strength and direction of the tide. The source of this data was the Dutch Hydrographic Office and these roses had proved invaluable on the earlier North Sea Archaeological Group expeditions.

The tidal regime can be summarized as consisting of a short period of relatively clear water slack between HW-3½ and HW–1½ hours (flood tide) and a longer one of poorer visibility from HW+2 to HW+5 hours (ebb tide). The ebb tide dominates, as is commonly the case in the vicinity of an estuary (Schelde), and the different high water levels show a small diurnal effect on the tidal curve.

Commercial surface supplied diving operations are normally conducted in tidal flows of up to 1 knot. During neap tides (3.0m range) the rate does not exceed 1 knot and therefore for a period of several days diving operations are normally unrestricted by tide. During a mean tide the rate will exceed 1 knot for an hour or more either side of high and low water leaving a diving window of approximately 67 hours during each tidal cycle (12 h 20 m). During spring tides (4.4m range) both slack periods are shortened, the flood slack significantly so, resulting in a reduced diving window of about 5 hours each cycle.

Underwater Visibility

Underwater visibility is frequently zero but can reach 7 or 8 m on several occasions during the summer months. The average conditions to be expected are 1m or less at seabed level. Ambient light levels are usually sufficient to allow vision without lighting after several minutes of adjustment, but at times the seabed is a dark environment so underwater lighting is therefore essential.

In general, the factors that will enhance underwater visibility are a prolonged period of light or westerly (onshore) winds and weak tides. The best visibility normally occurs within the period HW –3 to HW +1.

Another factor affecting the underwater visibility is the large amount of spoil dumped at sea by dredgers operating in the area.

Wind and Sea ConditionsSea conditions are largely wind driven and therefore can change in a matter of a few hours. Rough seas and swell may develop in any month of the year however as Atlantic depressions track across the region causing winds to blow mainly from the SW which then veer to NW.

Prolonged NW to N winds will cause a moderate to heavy swell and disturbed sea conditions along the Dutch and Belgian coasts which can persist for several days with only temporary lulls and changes in direction. Additionally, a marked sea breeze effect is often observed during anti-cyclonic conditions (high pressure) which increases wind speeds during the late morning and afternoon. The Terschelling was moored with the bows heading in a SW direction, thus facing the predominant weather.

Diving Procedures

Paul Dart

Equipment

All diving was carried out from the dive support vessel Terschelling using the air spread fitted to the vessel. This comprised:

• Low pressure compressor supplying three air diving panels

• A large high-pressure air bank which was fed from a high-pressure compressor

• Reduced high pressure from the bank supplying the air diving panels

• A high-pressure cylinder filling station on deck fed from the high-pressure compressor

• A twin lock 54” recompression chamber fed from both low pressure and high-pressure compressors

• Large back-up high pressure cylinders on deck for the panels

• 3 air diving umbilicals

• 3 Kirby Morgan Band mask helmets and one Kirby Morgan ‘Superlite’ helmet

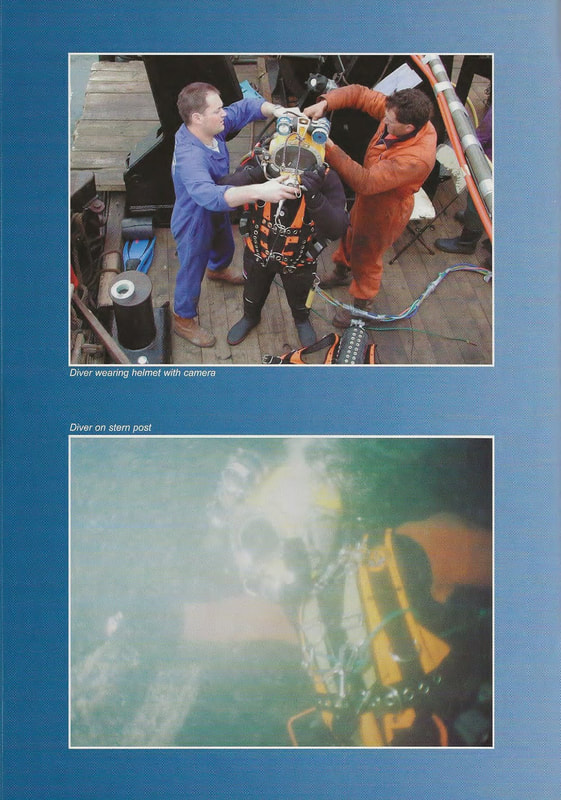

• Umbilical camera and light for the helmet fed to a video recorder, video capture card and monitor

• Diver’s cage and clump-weight operated from deck winch

• Closed-circuit TV for deck observation from Dive Control

• Deck communications via a transceiver

• Two six-inch and two four-inch airlifts

• Two road compressors feeding the airlifts

In addition to the diving spread there was support from the remote operated vehicles (ROVs) the Slingsby Seacat and the Hydrovision Hyball (Photo 7).

Methodology

Archaeological operations were carried out under the direct control of Alex Hildred as the Archaeological Director. All diving was controlled by Dive Supervisors appointed by Stephen Roue, Operations Manager for Falmouth Divers Ltd. All operations were carried out under the proposed and agreed Diving Plan submitted by Falmouth Divers Ltd.

The work was divided into three main operations with all of the operations being carried out simultaneously:

• Survey

• Excavation

• Recording and passive holding of artefacts

Terschelling was secured on a four-point mooring that made for very safe and relatively easy diving.

All diving equipment was inspected and checked against a list daily. The diving supervisor drew up a dive plan that fitted with individual abilities and skills and this was discussed with Captain Nigel Boston acting as Dive Project Coordinator. The plan had to fit in with the local tidal current and weather conditions. Assistance given by Mark Fuller was a major factor in the understanding of local conditions.

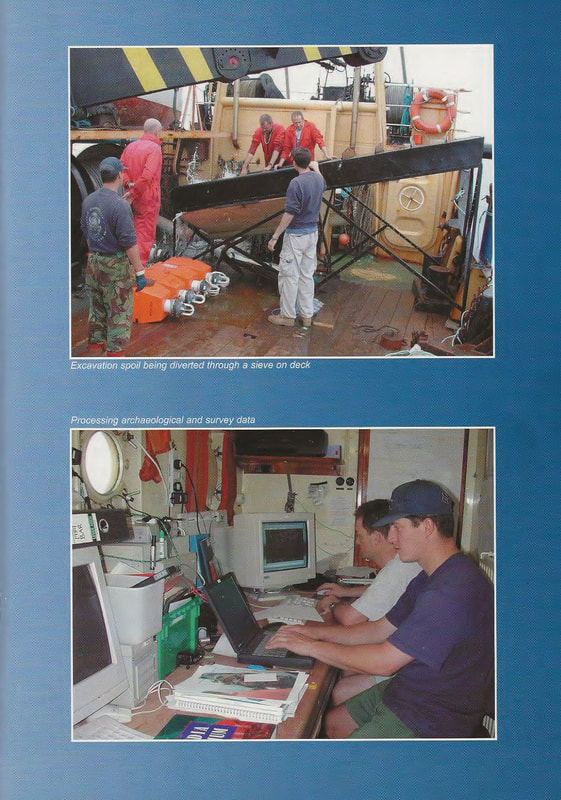

Most of the dives undertaken included excavation using the six-inch airlifts connected to the sieve. Problems with the airlifts were usually rectified by recovering the airlift and making changes on deck.

Divers were usually excavating alone, only on a few occasions were two divers in the water simultaneously, usually for the purpose of surveying. All diving was through a dive cage lowered from the deck. The standby diver stayed on deck along with the support team while the diving supervisor remained on the panel during diving operations with a deck supervisor overseeing the dressing, deployment, operation and recovery of each diver. Co-ordination with the deck banksman was via a deck transceiver that was operated from Dive Control.

Some recording of detail by video and stills photography was carried out. The camera on the Superlite helmet was used to record each dive, this proved to be important not only as a safety feature. The camera was used for recording the activities underwater allowing the archaeologists more control over the dive. Other tasks apart from airlifting and photography included the use of acoustic and tape measuring techniques to support the survey operations.

Holding facilities were prepared in order to provide conditions to inhibit further physical, biological or chemical deterioration of the artefacts.

Following registration, documentation and photography, all finds were stored for transport to the conservation facility at the Stedelijk Museum in Vlissingen. Under the direction of the conservator Ton van der Horst, intervention was kept to a minimum and the storage medium chosen was based on material type.

Cleaning was reduced to what was required for identification, measuring and photography and undertaken with a soft bristle brush. Any artefact with a residue which was presumed to be organic in nature, whether on the outside surface (paint, textile) or on the inside (packaging, organic contents) was not washed, but heat sealed within polythene or sealed within a strong zip polythene bag.

• All metals, ceramics and stone were stored in saltwater

• Wood, leather, bone or horn was sealed in polythene within a limited amount of seawater

• Textile and organic material was not re-immersed, but kept damp and sealed

The storage areas were located about the vessel in numbered tanks, all were within darkened areas and the large seawater tank was insulated. Where support was required, small containers with saturated foam were utilized.

Conservation

Ton Van der Horst

Procedure

As soon as the vessel docked all finds were transported to the conservation facility at the Stedelijk Museum in Vlissingen. They are cleaned and separated into material types before conservation. Any unphotographed artefacts are photographed. Anything missing from the artefact registration form is added at this stage.

Wood and leather are placed immediately into a large freezer, or tank containing fresh water if they are too large for the freezers. Once the organics have been frozen, water is removed by placing them in a vacuum freeze-drying chamber (Edwards BF 4) which can extract 1.2 kg of ice in 12 hours. After freeze-drying, wooden artefacts are treated with linseed oil to prevent any further drying or collapse. Leather is freeze-dried, but a specific leather dressing is applied once they are dry. If possible, reconstruction is undertaken at this stage.

Both complete and incomplete wine bottles are washed in tap water, as are all glass artefacts. This is undertaken within a circulation tank where the water is filtered. Routine readings for chlorides are taken. When the reading is stable, suggesting that there are no more chlorides within the glass, the artefacts are washed in distilled water until the chloride reading is less than 20 parts per million. The glass is then dried and immersed into a 1/10 solution of Dormoplast SG Normal that provides a coating. Any corks are treated with a two-part glue to prevent shrinkage.

Earthenware, stoneware and porcelain are washed in distilled water and dried. After each excavation season all the fragments from each trench are gathered together to try and piece together any vessels.

Bronze, silver, copper, brass and pewter are cleaned in an electrolytic tank using a 5% sodium hydroxide solution with the object forming the anode attached to a stainless-steel cathode. A 5 volt electrical supply is used. Following electrolytic reduction, the objects are neutralised and cleaned ultrasonically at between 40 - 70 degrees centigrade by turning a power supply on an off in intervals of not longer than five minutes. This short interval is necessary to prevent cavitation occurring which could damage the object. After the object is dry it is lacquered with Pantarol.

Gold is cleaned in an 85% solution of nitric acid, neutralised, ultrasonically cleaned and dried.

Steel and cast iron are treated by immersion in a 63 gram per litre solution of sodium sulphite which is covered and heated to 70 degrees celcius and constantly mixed. The solution is changed weekly following routine chloride readings. Once the readings remain below 100 parts per million, the objects are considered stable. The remaining chlorides have changed into barium sulphate. The object is then dried and placed in melted microcrystalline wax.

Reconstruction

All incomplete objects are studied with their associated objects. Any broken objects which can be reconstructed are put together. Objects which have been damaged or bent such as pewter plates are carefully reconstructed to show their original form and placed on display to tell their own story. Photo 37 shows reconstructed lanterns from previous excavations and a conserved oil lamp from the 2000 season.

Project Statistics

Mark Fuller

Tidal ConditionsA set of tidal roses for the area surrounding the Vliegent Hart site based on the standard port of Vlissingen, Netherlands, were used to predict the strength and direction of the tide. The source of this data was the Dutch Hydrographic Office and these roses had proved invaluable on the earlier North Sea Archaeological Group expeditions.

The tidal regime can be summarized as consisting of a short period of relatively clear water slack between HW-3½ and HW–1½ hours (flood tide) and a longer one of poorer visibility from HW+2 to HW+5 hours (ebb tide). The ebb tide dominates, as is commonly the case in the vicinity of an estuary (Schelde), and the different high water levels show a small diurnal effect on the tidal curve.

Commercial surface supplied diving operations are normally conducted in tidal flows of up to 1 knot. During neap tides (3.0m range) the rate does not exceed 1 knot and therefore for a period of several days diving operations are normally unrestricted by tide. During a mean tide the rate will exceed 1 knot for an hour or more either side of high and low water leaving a diving window of approximately 67 hours during each tidal cycle (12 h 20 m). During spring tides (4.4m range) both slack periods are shortened, the flood slack significantly so, resulting in a reduced diving window of about 5 hours each cycle.

Underwater Visibility

Underwater visibility is frequently zero but can reach 7 or 8 m on several occasions during the summer months. The average conditions to be expected are 1m or less at seabed level. Ambient light levels are usually sufficient to allow vision without lighting after several minutes of adjustment, but at times the seabed is a dark environment so underwater lighting is therefore essential.

In general, the factors that will enhance underwater visibility are a prolonged period of light or westerly (onshore) winds and weak tides. The best visibility normally occurs within the period HW –3 to HW +1.

Another factor affecting the underwater visibility is the large amount of spoil dumped at sea by dredgers operating in the area.

Wind and Sea ConditionsSea conditions are largely wind driven and therefore can change in a matter of a few hours. Rough seas and swell may develop in any month of the year however as Atlantic depressions track across the region causing winds to blow mainly from the SW which then veer to NW.

Prolonged NW to N winds will cause a moderate to heavy swell and disturbed sea conditions along the Dutch and Belgian coasts which can persist for several days with only temporary lulls and changes in direction. Additionally, a marked sea breeze effect is often observed during anti-cyclonic conditions (high pressure) which increases wind speeds during the late morning and afternoon. The Terschelling was moored with the bows heading in a SW direction, thus facing the predominant weather.

Diving Procedures

Paul Dart

Equipment

All diving was carried out from the dive support vessel Terschelling using the air spread fitted to the vessel. This comprised:

• Low pressure compressor supplying three air diving panels

• A large high-pressure air bank which was fed from a high-pressure compressor

• Reduced high pressure from the bank supplying the air diving panels

• A high-pressure cylinder filling station on deck fed from the high-pressure compressor

• A twin lock 54” recompression chamber fed from both low pressure and high-pressure compressors

• Large back-up high pressure cylinders on deck for the panels

• 3 air diving umbilicals

• 3 Kirby Morgan Band mask helmets and one Kirby Morgan ‘Superlite’ helmet

• Umbilical camera and light for the helmet fed to a video recorder, video capture card and monitor

• Diver’s cage and clump-weight operated from deck winch

• Closed-circuit TV for deck observation from Dive Control

• Deck communications via a transceiver

• Two six-inch and two four-inch airlifts

• Two road compressors feeding the airlifts