History of the VOC

Jan Pieterszoon Coen

Jan Pieterszoon Coen, oil painting, 17th century.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Jan Pieterszoon Coen

Jan Pieterszoon Coen, oil painting, 17th century.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

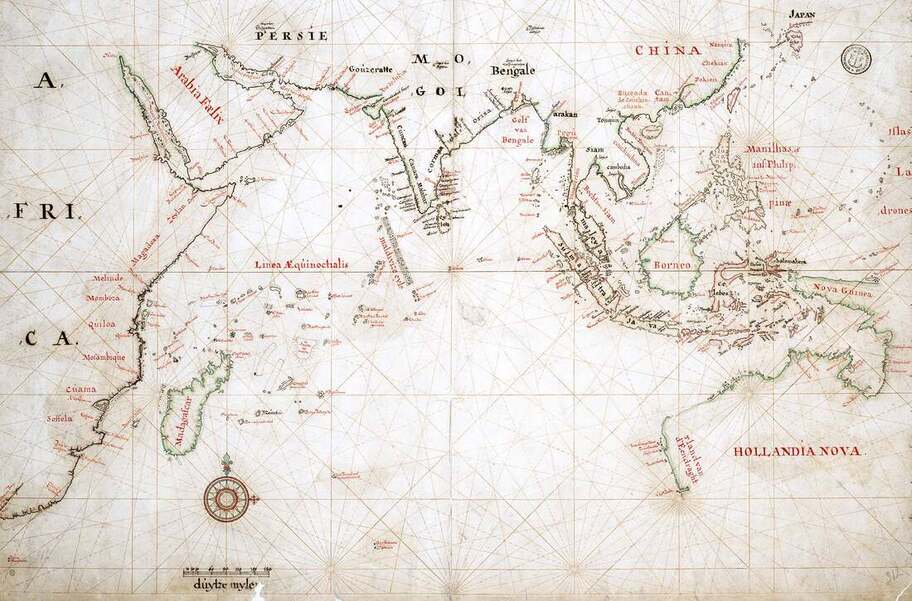

The Dutch East India Company, officially the United East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie; VOC) was an early megacorporation founded in 1602 by a government directed amalgamation of several rival Dutch trading companies.The Dutch government granted the company a trade monopoly in the waters between the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa and the Straits of Magellan between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans with the right to conclude treaties with native princes, to build forts and maintain armed forces, and to carry on administrative functions through officials who were required to take an oath of loyalty to the Dutch government. Under the administration of forceful governor-generals, most notably Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1618–23) and Anthony van Diemen (1636–45), the Company was able to defeat the British fleet and largely displace the Portuguese in the East Indies.

During the 17th and 18th centuries the VOC was the largest trading company in the world and had a fleet that ranged from Aden and Persia eastwards to Korea and Japan, with over 250 trading stations within the network.

The VOC traded until 1799, although in the end a diminished and nationalised company, the VOC is recognised as the world's first formally listed public company, having undertaken the world's first recorded IPO in 1602. From the foundations of the VOC institutions, has risen the modern-day global corporations and capital markets which now dominate global economics.

During the 17th and 18th centuries the VOC was the largest trading company in the world and had a fleet that ranged from Aden and Persia eastwards to Korea and Japan, with over 250 trading stations within the network.

The VOC traded until 1799, although in the end a diminished and nationalised company, the VOC is recognised as the world's first formally listed public company, having undertaken the world's first recorded IPO in 1602. From the foundations of the VOC institutions, has risen the modern-day global corporations and capital markets which now dominate global economics.

|

Following the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), two or three fleets would sail each year from the Dutch Republic to Asia. Bigger ships were built for the voyage, to carry more people and more produce. It generally took eight months to reach the East Indies. An average of seven knots (13 kilometres per hour) was considered a good speed. Along the route, the VOC set up trading posts where ships could take on provisions for the next stage. Between 1602 and 1610, 8,500 people sailed to the East. The numbers soon rose: in the 17th century an average of 4,000 people sailed to East Asia each year; and in the 18th century even more. East Indiamen could carry hundreds of passengers. The ship’s company of sailors and soldiers slept tightly packed between decks, where it was close and foul. No thought was given to hygiene. Officers, the captain and passengers occupied cabins on the quarterdeck. Discipline was severe on board. It had to be. Sailing to Asia was a dangerous undertaking, and often difficult as well as tedious. For the long voyage to Asia and back the Dutch East India Company (VOC) built special ships. These were a combination of cargo and battleship: sturdy and with a large hold for produce, as well as provisions and ammunition. The wood and ropes suffered wear and tear on the voyage too. At the shipyard in Batavia the ships were overhauled - careened and cleaned - to ensure they were in a suitable condition for the voyage home.

|

For two-and-a-half centuries, the Dutch were the only Europeans permitted to trade in Japan. And even there they were confined to a small artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki: Deshima. Europeans were barred from entering Japan; and the Japanese from leaving. However, once a year, a small Dutch delegation would make its way to Tokyo to thank the Shogun for the privileged position that the Dutch enjoyed – and to present gifts of course. Goods were transported across a bridge connecting Deshima with the city and this was how the Dutch learned about Japanese culture. Among the Japanese it gradually became evident that there was a world out there. A world in which discoveries were made, and progress, while Japan stood still. Dutch atlases and globes were a particular source of fascination in Japan. For the rest, the Dutch were considered uncivilised and especially ill-mannered at table.

By the late 17th Century the Company had declined as a trading and sea power and had become more and more involved in the affairs of Java. |

By the 18th Century the Company had changed from a commercial shipping enterprise to a loose territorial organisation interested in the agricultural produce of the Indonesian archipelago. Toward the end of the 18th Century the Company became corrupt and seriously in debt. The Dutch government eventually revoked the Company’s charter and in 1799 took over its debts and possessions, after 297 year of trading this was the end for the VOC.